French fries, potato chips, pretzels, nut mixes, popcorn, pizza, and more. We love them for their great taste, much of which comes from the added salt. Indeed, we need some salt to survive, and our brains are hardwired to crave it. Getting too much, however, may increase our risk of disease.

The 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend that we consume less than 2,300 milligrams (mg) of sodium each day as part of a healthy eating pattern. That’s equal to only about one teaspoon per day. Yet according to studies, Americans eat much more than that, with the average daily intake being more than 3,400 mg.

Excess sodium in the diet has been linked with cardiovascular disease and other health problems for decades. Recent research, however, has cast doubt on just how much sodium is too much.

This brings us to one question: Should you be cutting back on your sodium intake or not?

What is the Difference Between Sodium and Salt?

Before we get into the nitty-gritty on sodium, it's important to understand the difference between sodium and salt. Though the terms are often used interchangeably, they are not the same.

What is Sodium?

Sodium is an essential mineral that we can't live without. We must get it from the diet for our bodies to function correctly.

Sodium acts like a mineral and an electrolyte in the body. It helps keep fluids in normal balance, conduct nerve impulses, and contract and relax muscles. Most of the sodium in the body (about 85 percent) is found in blood and lymph fluid. A hormone called aldosterone helps control the sodium levels, telling the kidneys when to retain or dispose of it.

Sodium is found naturally in some foods and is added to others during manufacturing. Celery, beets, and milk all naturally contain sodium. Canned soups, lunch meats, and frozen dinners typically have sodium added during manufacturing. The American Heart Association (AHA) states that overall, about 70 percent of the sodium we eat comes from processed, prepackaged, and restaurant foods.

What is Salt?

Salt is a crystalline mineral composed of sodium and chloride. Ordinary table salt is only about 40 percent sodium and 60 percent chloride. So when you use table salt on your food, you’re getting some sodium, but often not as much as you get when you eat processed and restaurant foods.

Salt occurs naturally in many parts of the world. Seawater, for instance, contains a lot of salt, whereas underground salt deposits are found in both bedded sedimentary layers and domal deposits. Some salt exists on the Earth’s surface, such as on the dried-up residue of ancient seas like the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah.

Since salt is only 40 percent sodium, here's a trick you can use to see how much salt you're consuming in a product that lists only “sodium” on the label: multiply that sodium number by 2.5.

How Sodium Affects the Body

We need some sodium for fluid balance and muscle and nerve function. If we get too much, the body flushes out the extra via the urine. This is why you may feel thirsty when eating salty foods. Your body recognizes the excess sodium and calls for water to help the kidneys flush it out.

If you’re not getting enough sodium, you may feel the following symptoms:

- Hyponatremia (a low-sodium condition)

- Dizziness

- Confusion

- Feeling sluggish and lethargic

- Muscle twitches

- Seizures

Consuming too much sodium over a long period has been linked to:

- Kidney stones

- High blood pressure

- Cardiovascular disease

- Osteoporosis

- Stroke

Though the kidneys help regulate the level of sodium in the body, if you regularly consume too much, it’s possible to overwhelm them so they can’t keep up. That can leave excess sodium in the blood, which then pulls water out of the cells to compensate. As this water increases, so does blood volume. That requires the heart to work harder to pump all that blood around and also increases pressure in the blood vessels.

Over time, this process can damage the blood vessels, causing them to stiffen and become less flexible, which leads to high blood pressure and an increased risk for heart attack and stroke.

Excess sodium in the diet has also been shown to overstimulate the immune system, which could increase the risk of autoimmune diseases like lupus, multiple sclerosis, allergies, and other similar conditions.

The Confusion on How Much Salt is Too Much

Most scientists and doctors believe that consuming too much sodium is bad for your health, particularly your cardiovascular health. This belief is based on decades of research connecting high-sodium diets with an increased risk of high blood pressure and damaged blood vessels.

Because of these findings, major health organizations have long recommended that Americans cut back on their sodium intake.

Some recent studies have cast doubt on this idea, however. In one of them, scientists analyzed data from over 95,000 people in 369 communities across 18 countries to examine the relationship between sodium intake and cardiovascular disease. They followed the participants for a median of about 8 years.

The results showed that people in China had the highest sodium intake—a mean of greater than 5 grams per day. In other countries, the mean intake was 3-5 grams per day. More importantly, sodium intake was positively associated with high blood pressure only in those communities where the mean intake was greater than 5 grams per day. The researchers also found that very low intakes of salt actually led to more heart attacks and death than too much salt, suggesting that moderate salt intake may be protective.

Study author Andrew Mente stated, “Our study adds to growing evidence to suggest that, at moderate intake, sodium may have a beneficial role in cardiovascular health, but a potentially more harmful role when intake is very high or very low.”

The scientific journal, Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, also published an article about the sodium debate, which noted several other studies producing conflicting results on the harmful effects of excess sodium. Some challenged the current emphasis on restricting sodium. Others found that excess sodium increased the risk of not only cardiovascular disease but death from cardiovascular outcomes (like heart attack and stroke).

Confused? You’re not alone.

Not Everyone Is Equally Sensitive to Sodium Excess

Clarity may be found in our individual differences. It seems that some of us may be more sensitive to excess sodium than others. Just as scientists have found that our genes can affect how sensitive we are to caffeine, so have they found that our genes can make us more sensitive to sodium in the blood.

Harvard Health notes that those who are especially sensitive to sodium—their blood pressure rises and falls directly with their sodium intake—are more likely to suffer an increased risk for cardiovascular disease if they eat a high-sodium diet.

Although anyone may be sensitive to sodium intake, those most prone to it include:

- The elderly

- African Americans

- People who already have high blood pressure

- Those with diabetes

- Those with kidney disease

- Those whose genes make them salt-sensitive

Interestingly, scientists have discovered that many of the genes that play a role in salt sensitivity also play a role in the complex control of blood pressure. Studies suggest that variants of the ACE and AGT genes may predispose people to salt sensitivity. Other genes involved in blood pressure regulation include NOS3 and others.

If you take all these groups together, you can see that there remains a large section of the population that is salt-sensitive and needs to be careful about sodium intake.

7 Signs You May Need to Reduce Your Sodium Intake

7 Signs You May Need to Reduce Your Sodium Intake

1. You’re salt-sensitive.

So far, there is no test to determine whether you may be salt-sensitive. The only way to tell is to keep an eye on your blood pressure levels. If you have an at-home blood pressure testing machine, test your levels about 30 minutes before eating, then again 30 minutes after eating. Compare the results. If you note a 5-10 percent increase in blood pressure, you may have a salt sensitivity.

Sometimes doctors will have patients try a low-sodium diet containing no more than 230 mg of sodium for four days, then switch to a high-sodium diet containing about 4.6 grams of sodium over the next four days, and check blood pressure levels at each point to note any changes. If the blood pressure increases significantly between the first and the second diet, the person may be diagnosed with salt sensitivity.

2. You have high blood pressure.

If you already have high blood pressure, excess sodium is not good for you. Your blood vessels are already damaged and your heart is working harder to pump blood through them. If you add excess sodium to the mix, you’ll be making the situation worse and potentially accelerating cardiovascular damage.

3. You are African American.

3. You are African American.

Studies have linked being African American with a higher risk of being salt-sensitive. There is also a high prevalence of high blood pressure in African Americans.

The Office of Minority Health (OMH) notes that in 2018, African Americans were 30 percent more likely to die from heart disease than non-Hispanic whites. They were also 40 percent more likely to have high blood pressure and were less likely than non-Hispanic whites to have their blood pressure under control.

African American women were in even more danger—60 percent were more likely to have high blood pressure, as compared to non-Hispanic white women. And according to one study published in Hypertension, salt sensitivity was found in 73 percent of hypertensive and 36 percent of African Americans with normal blood pressure.

4. You’re 60 or older.

As we age, we are more likely to have high blood pressure. That is reason enough to cut back on sodium. Some older people are also more likely to be salt-sensitive. In one study published in The American Journal of Cardiology, researchers noted that hypertension in the elderly is generally of a salt-sensitive nature. Researchers echoed this finding in a later 2018 study.

Aging can also affect kidney function, meaning that the kidneys may not be as effective at flushing away excess sodium.

Even if you don’t have high blood pressure, realize that age may increase your sensitivity to salt. In a 2009 study, researchers examined salt sensitivity in older people who were not hypertensive. They found that a high-salt diet led to a significant increase in blood pressure levels in sensitive people, even if they had normal blood pressure levels to begin with.

5. You’re suffering from Edema.

5. You’re suffering from Edema.

Edema is swelling caused by excess fluid trapped in the body’s tissues. As mentioned above, eating too much sodium can increase the fluid in the blood, and is a primary cause of Edema. The swelling most often occurs in the feet, ankles, and legs, but may also occur in the hands, arms, and other areas of the body.

6. You suffer from kidney stones.

A diet high in sodium can, as we’ve learned, damage the kidneys and hinder kidney function. In addition to requiring the kidneys to work harder to flush out the excess, it can also increase the amount of calcium in the urine, which can, in turn, increase the risk that kidney stones will form.

7. Your digestive system is struggling.

If you have a stomach ulcer, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), heartburn, bloating, and other digestive upsets, you may suffer worse symptoms when you consume a lot of sodium. Recent research has found that a high-sodium diet can harm the gut microbiome (the balance of bacteria in the stomach and intestines).

There is also evidence that a high-sodium diet may increase inflammation in the gut, potentially damaging the lining and leading to digestive ailments. In a 2019 study, researchers found that individuals reported more bloating when they ate a high-salt diet.

10 Tips for Cutting Back on Sodium

10 Tips for Cutting Back on Sodium

If one or more of the above situations apply to you, or if you want to cut back on sodium for general health reasons, try the following tips.

1. Cut back on the saltiest foods.

We know that the following foods are some of those with the most sodium. Try cutting back on these, or looking for low-sodium alternatives.

- Bread and rolls

- Pizza

- Fast food cheeseburgers/sandwiches

- Cold cuts and cured meats

- Canned and boxed soup

- Burritos and tacos

- Snack foods (chips, crackers, microwave popcorn, pretzels)

- Chicken (includes processed chicken)

- Cheese (includes processed cheese)

- Egg dishes and omelets

2. Prepare your own food when you can.

2. Prepare your own food when you can.

Most of our sodium comes from convenient, processed foods and snacks. These include chips, crackers, crisps, and ready meals. Packaged sauces, mixes, and instant products are also typically high in sodium. Choose to prepare your meals at home with wholesome ingredients when you can.

3. Eat mostly fresh foods.

The more fresh (and wholesome frozen) foods you eat, the lower your sodium intake will be. Start with unsalted, fresh foods and prepare them yourself.

4. Be careful with condiments.

Many common condiments, including soy sauce, Worcestershire sauce, salad dressings, ketchup, seasoned salts, and more are high in sodium. Look for low-sodium alternatives and try to useless. Keep in mind that monosodium glutamate (MSG) also contains sodium.

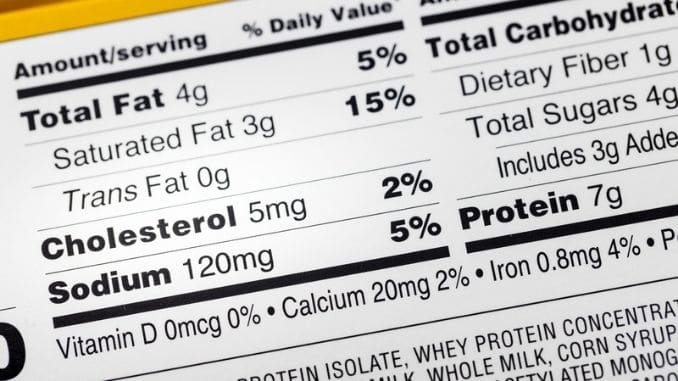

5. Read labels.

Food labels have to list the level of sodium per serving, so check those labels carefully to be sure you’re not getting a high-sodium food. A good rule of thumb is to ensure each serving of food has less than 100 mg of sodium.

You can also look for foods that have the following terms on them:

- Sodium-free or salt-free (each serving contains less than 5 mg sodium)

- Very low sodium (each serving contains 35 mg of sodium or less)

- Low sodium (each serving contains 140 mg of sodium or less)

- Reduced or less sodium (at least 25 percent less sodium than the regular version)

- Lite or light in sodium (sodium content has been reduced by at least 50 percent from the regular version)

- Unsalted or no salt added (no salt is added during processing, though some ingredients may still be high in sodium)

6. Rinse canned products before eating.

6. Rinse canned products before eating.

Canned veggies, beans, and other items are often high in sodium. You can simply rinse them off before preparing them, which can cut up to 40 percent of the added sodium out.

7. Experiment with other spices.

To flavor your food at home, experiment with other options like dried or fresh herbs, spices, and zest and juice from citrus fruits.

8. Use salt substitutes wisely.

There are many salt substitutes on the market today to help satisfy consumers’ demand for lower-sodium options. Read the labels carefully and make sure these work for you. If they don’t provide enough flavor and you use more as a result, you could still be getting too much salt.

Some of these substitutes include potassium, too, which can help manage sodium levels. But too much potassium can be damaging, so check with your doctor to be sure.

9. Remove salt from recipes when possible.

Most recipes call for salt, but you don’t always need it. Good salt-free options include casseroles, soups, stews, and other main dishes. Look for cookbooks that are made for those wanting to lower their blood pressure or manage heart disease.

10. Make lower-sodium choices at restaurants.

Restaurants are notorious for using lots of salt and sodium in their foods. Ask to have your meal prepared with less salt. Ask for sauces and salad dressings to be served on the side, then use less of them. Also, ask if the nutrition information is available for the menu items. You may also be able to find them online at the restaurant's website.

Remember, your body does need some sodium to function optimally, but most people consume far more than the recommended daily amount. We live in a world of convenience, and often faster foods have the most sodium content. Be aware of what you are eating and make conscious, lower-sodium choices whenever possible. Don’t wait until you are in a health crisis before taking active steps towards better nutrition.

Remember, your body does need some sodium to function optimally, but most people consume far more than the recommended daily amount. We live in a world of convenience, and often faster foods have the most sodium content. Be aware of what you are eating and make conscious, lower-sodium choices whenever possible. Don’t wait until you are in a health crisis before taking active steps towards better nutrition.

Learn the best ways to fuel your body safely, allowing you to finally lose those stubborn pounds. Click here for more info.